Public Health Students Generate COVID-19 Questions and Answers

Working with public health students in her Epidemiology 479 class, Kate Ellingson, Assistant Professor, developed a collection of Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) with answers related to COVID-19 and the preventive measures used to slow the spread of the virus. All the answers were drawn from the best scientific studies available.

Q: How can I stay calm and help others from freaking out about the unknown?

A: Managing generalized anxiety and mental health is critical. As a starting point, here is some basic guidance from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Lots of great resources in that doc addressing the following:

- Understand that reactions such as fear, anxiety, loneliness, anger, and boredom are normal, but everyone will react differently

- Educate yourself and know your risk

- Stay connected and advocate for your needs

Q: Say if someone sneezes and they have the virus, how long could the virus live on an object, for instance a shirt?

A: Recent research indicates that the virus can live on stainless steel, cardboard and plastic for hours (around 4-7h, but up to 72) depending on the concentration of virus, per a New England Journal of Medicine study. So the answer to your question depends on the type of surface and the infectious dose deposited on a surface. Bottom line is that the virus can live on surfaces so we should be mindful of fomite transmission. Just as healthcare workers change gowns, washing clothing after being out and about or after a potential exposure makes sense.

Q: Are there different symptoms that someone could develop while having the virus?

A: Absolutely, symptoms manifest differently and range from none, mild, moderate, and severe. CDC’s page focuses on fever, cough, and shortness of breath, but we know that there are a variety of manifestations, including diarrhea and runny nose. We are learning more about how symptoms may manifest differently in different populations. E.g., persistent low-grade respiratory symptoms without fever on a cruise ship and nausea and vomiting in children.

Q: I've heard the CDC saying something about "flattening the curve" can you explain that?

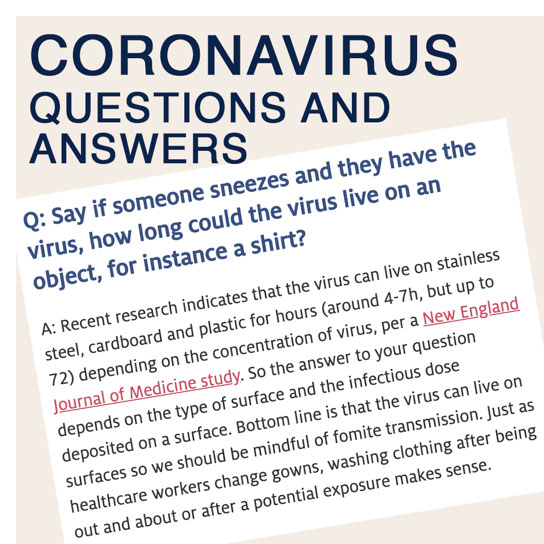

A: Flattening the curve refers to taking action to slow transmission so that our healthcare system can handle the surge of severe cases. These severe cases represent the tip of the iceberg of cases. Given the projected exponential growth of all cases, the tip of the iceberg (~20% need hospitalization) will quickly overwhelm our healthcare system. Here is a projection from Arizona – a data visualization based on inputs from modelers at Columbia University. We will review the model inputs in class. Keep in mind that models do not predict the future, but they can help us make decisions based on what we know now, even when that information is incomplete. We'll discuss each of the assumptions inherent in this model.

Q: I heard that eyes can act as a portal of entry, is this true? And if it is true, what can we do to protect ourselves?

A: As with all pathogens transmitted by droplets, the eyes represent a mucous membrane though which a pathogen can enter. There is also some evidence that SARS-CoV-2 is present in tears. Because SARS-CoV-2 is droplet-borne, the eyes can serve as a portal of entry. If you work in a healthcare setting (and some of you do), wearing eye protection or a face shield is ideal.

Q: I have a newborn sister and what are some ways I can make sure I won’t transmit the virus to her in case I am asymptomatic?

A: Although severe cases of SARS-CoV-2 in infants and children is low, we are still learning about the risk, and we know that neonates are, in fact, susceptible to infection. As we discussed, the data out of China may not reflect true risk in the pediatric population given how isolated children were due to holidays, closures, and isolation of sick adults and healthcare workers apart from their families. To be safe, I would recommend vigilant infection prevention practices in your household. Monitor your own health and self-isolate at the first sign of symptoms, practice strict hand hygiene social distancing when possible. Keep high-touch surfaces disinfected.

Q: I work at a rehab center where my patients are typically older adults.

A: Work with your employer to determine which procedures are essential and scale back on contacts that are non-essential. Vigilant self-monitoring for symptoms is critical (self-isolate at the first sign), frequent hand hygiene, following the WHO’s 5 Moments for Hand Hygiene. Wear PPE – use masks if available, eye protection, gloves and gowns. Try not to touch your mask (follow standard protocols for putting on and taking off PPE). Change gloves and gowns between patients. Here is CDC guidance for healthcare settings.

Q: Can you show some symptoms without showing all symptoms, such as a cough without fever and so on?

A: Absolutely (see previous answer). Importantly, those showing no symptoms can transmit the virus. This phenomenon has been key to the rapid rise in cases.

Q: How long do you think the self-quarantine will continue for, especially since with "flattening the curve" the virus will exist longer within our community?

A: We don't know. You can see the projection for Arizona (above) but this model is based on assumptions that could change. You are correct that flattening the curve draws out the case surge over a longer period of time, as social distancing is designed to do. Given our poor handle on the actual case count, the outbreak peek is really a “best guess” but one informed by poor data on case counts.

Q: Is it only children that can spread the virus through feces or can adults shed it this way as well?

A: Adults can also shed virus in feces. In fact, the first case in the US demonstrated positivity in the fecal sample. We do not yet know whether or how much fecal-oral transmission contributes to overall transmission.

Q: What would you say to someone who believes the flu is more dangerous than COVID19?

A: I would say there are several fundamental differences. First, none of us have pre-existing immunity to this novel coronavirus. For influenza, where most circulating strains are similar to strains we’ve seen before, most of us have partial immunity. Second, there is an influenza vaccine, and although far from 100% effective, it substantially lowers case counts and deaths. Third, we have Tamiflu (Oseltamivir) to ease symptoms and to give as prophylaxis to high risk groups. Also, given our current projections, COVID-19 can easily overwhelm healthcare systems if all cases are hospitalized over a short period of time. Case fatality rates are much higher than flu if hospitalization needs outstrip capacity. The case-fatality rate can be decreased if we spread the hospitalizations out over time.

Q: Have any rapid diagnostic tests been developed? Would these be most helpful for hospitals/healthcare centers in rural areas with their limited sources?

A: Rapid tests will be critical to minimizing the impact of this epidemic. There are rapid PCR tests (measuring viral load) in the works and there are early versions of rapid antibody tests available.

Q: What is your opinion on the Imperial College London study that came out a few days ago?

A: This was one of the earliest sophisticated models to come out. Models were initially specified for influenza and the scenarios they specified are now a bit out of line with our current response (e.g., social distancing but not closing of schools). These models need to be updated to reflect the current response.

Q: How much does the dose of exposure matter (i.e. "viral load")? What about "low-dose, repeat" exposures among asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic cases?

A: Can't say definitively yet, but the rates of infection in healthy healthcare workers suggests that viral load at infection matters. Also the majority of clusters identified are family clusters, indicating that "low-dose, repeat" exposures promote transmission among those who are mildly symptomatic or asymptomatic.

Q: If you get COVID19, would you be able to get it again or are you completely immune after surviving it?

A: We don't have a clear answer to this question yet. There have been reports of reinfection (e.g., this LA Times article highlighting case reports). There was some hopeful news out of a small macaque (monkey) study, showing that monkeys could not become re-infected. There are several issues to consider here. The first is that we do not have a great handle on the accuracy of tests. So "false negatives" could indicate that someone is "over" the illness when they are actually not. Symptomatic flare ups from the original infection could be interpreted as a new infection. See this JAMA research letter published on recovered COVID-19 patients again testing positive.

Q: Is it safe to take ibuprofen or other NSAIDs?

A: The theory that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen can exacerbate COVID-19 symptoms was first posited in a Lancet Research letter, positing that SARS-CoV-2 binds to target cells through angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). ACE2 is substantially increased in those with metabolic disorders (like diabetes) and its expression is increased with use of NSAIDs. Hence the hypothesis that NSAIDs increase infection. The FDA has issued an advisory on the use of NSAID, saying that while there is not scientific evidence to support this hypothesis, they are actively investigating. What they can say for sure is that: "the pharmacological activity of NSAIDs in reducing inflammation, and possibly fever, may diminish the utility of diagnostic signs in detecting infections." The British Medical Journal goes farther in recommending that symptoms NOT be treated with NSAIDs.

Q: Why do some people have symptoms and others do not?

A: We do not know all of the scientific mechanisms, but generally speaking people with co-morbidities have more severe symptoms. This could be due to a depressed immune system or expression of certain enzymes that allow the virus to more readily enter cells. People may have genetic variations that make them more susceptible. Finally, differences in the dose of virus upon infection may affect an individual's ability to fend off the virus, leading to more severe symptoms.

Q: How are models accounting for lack of testing?

A: This is tricky. Some don’t try to account for the lack of testing and take testing at face value. A modeling group out of Columbia that has created the “actnow” models, uses a multiplier of 11 to account for lack of testing (for every 1 confirmed case, there are 11 undetected). This is an estimate, however, and its accuracy changes daily with changes in testing protocols.

Q: I have heard there is a shortage of ammunition and people are buying more guns. I understand that people want to protect their families but I am worried about inter-personal violence.

A: This is highly worrisome. There are efforts throughout the country to provide housing (e.g., vacant hotels) to people experiencing domestic violence or homelessness. As a public health community, we need to be thinking about these effects of social distancing measures and actively pursue solutions to mitigate dangerous situations.

Q: What is the difference between social-distancing, self-isolation, and self-quarantining.

A: Social distancing is the practice of maintaining physical space (6 feet) between others as much as possible to reduce transmission. Self-isolation refers to staying home and taking precautions when sick. Self-quarantine refers to staying home and taking precautions while well, but concerned about an exposure.

Q: Why are test kits so limited in the United States?

A: I don't have a good answer for this. What I do know is that communication from federal officials about test kit availability has been poor. Millions of test kits were promised weeks ago that did not materialize. Also, private and university labs were not allowed to test without FDA approval, which is a lengthy bureaucratic process. For these reasons, the criteria for getting tested has remained strict.

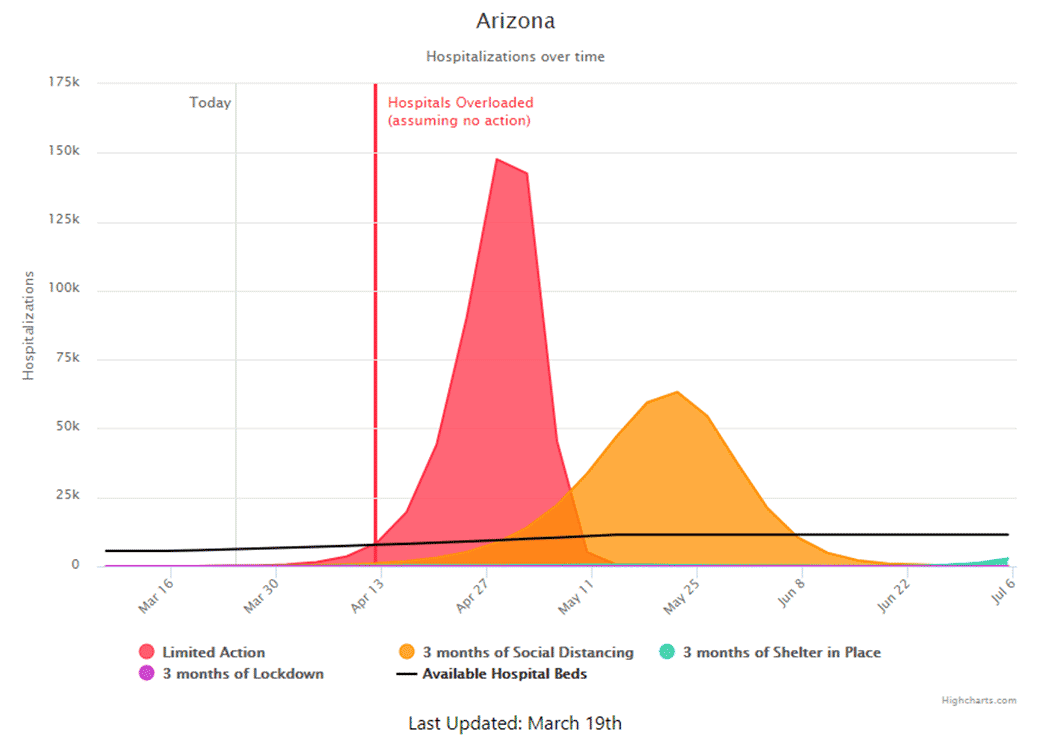

Q: What is the risk of young people getting severe disease?

A: Still low compared to older adults, but the risk is higher than the scientific community initially thought. A recently-published MMWR report shows that young people are experiencing severe outcomes in the US, albeit at lower rates than older individuals (be mindful of the age intervals on the x-axis of the graphic below):

Q: If we hear the spread of misinformation do we have a responsibility to say something, especially if it could be damaging?

A: Yes, as public health students and professionals, it is our responsibility to share our perspective in a respectful way. As we will discuss in our module on vaccine hesitancy, scorn and condescension only makes people less likely to hear our perspective. I found this article in The Atlantic useful. Strategies for getting people to take this pandemic seriously:

- (Gently) remind people that it's not all about them

- Avoid numbers; tell stories (this one is hard for me, but it’s true in this instance): “the narrative approach tends to resonate with people”

- Don't just ask people not to do something - ask them to do something else. Instead of "stop panic-buying" try "how about helping seniors by delivering groceries?"

- Don't forget to be nice

- Don't try to change people's worldview

- Consider your relationship with the listener

For an example of an empathetic and informational narrative approach, see this excellent 7-minute talk by an infectious disease epidemiologist and physician at U. Chicago.

And then, there is always the power of an image:

Q: What can we be doing to actively alleviate the spread of COVID-19?

A: For now, practice social distancing. Educate your friends and family members. Try to minimize your trips out (e.g., large shopping trips). You can offer to shop for friends or older neighbors. You can volunteer to help with the public health response. We will discuss options for the latter in class next week.

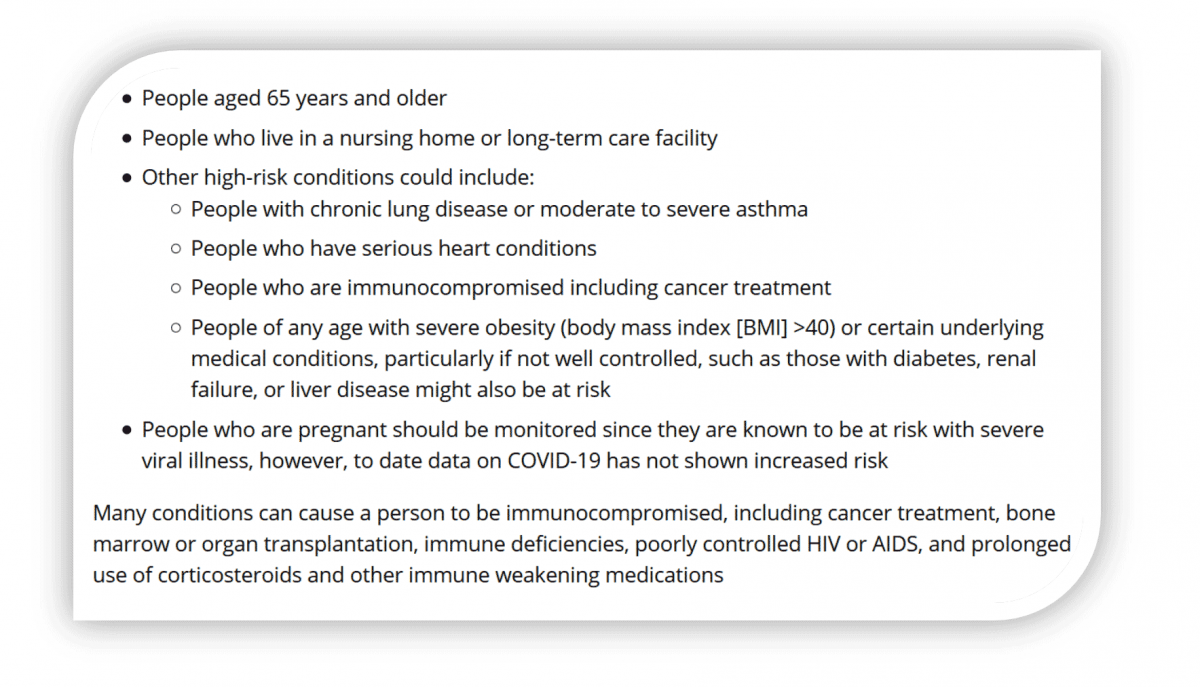

Q: What co-morbidities make people more susceptible to COVID-19?

A: We are learning more every day. Here is a CDC's current list:

Q: Why do they say not to touch your face when it's the mucous membranes they are concerned about?

A: The face is where there are lots of mucous membranes and we touch our face a lot, but technically speaking the message would be more accurate if it was “Do not touch eyes, nose, or mouth.” I think the "Don't touch your face" is simpler messages. Also, people may rest their hand on their cheek or rub their forehead, and inadvertently touch their eyes, nose, or mouth.

Q: Is it airborne or droplet?

A: The prevailing belief is that it is primarily droplet-borne, like the other human coronaviruses. However, there is emerging evidence that virus is shed in feces (indicating the possibility of indirect fecal-oral transmission) and that it can survive in aerosolized droplets for up to 3 hours (indicating that it can possibly transmit via the airborne route). The contribution of airborne transmission to the outbreak is unknown.

COVID covid coronavirus virus covid19 corona